Kyne's Challenge/Morrowind

Real author : David S. J. Hodgson (Writter), David Keen (Artist), Brynn Metheney (Artist), Roberto Gomes (Artist) Original media : The Hero's Guides to The Elder Scrolls Online Comment : This book is a trek across the provinces by a group of Nord hunters in honor of the Sky Goddess Kyne.

By Grundvik Cold-Fist, 2E 581

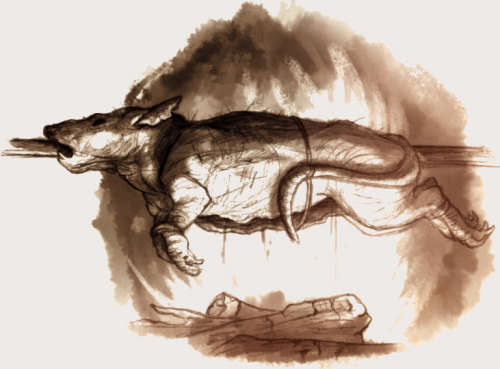

S KEEVER | At the edge of the Autumnal Forest with the Velothi Mountains at our backs, our previous night’s joviality had lessened considerably. Kishra-do joined us before departing for Mournhold, away from our hunt. Fenrig sat apart from us, bathed in a shaft of light from Secunda, keeping his dogs away from the Argonian and the Khajiit. Ingjard

sat pensively, quietly murmuring prayers to Kyne. Bashnag was out collecting firewood, his nighttime foraging exhibiting all the silent cunning of a mammoth in an apothecary. Kishra-do stopped chatting to Footfalls-in-Snow, and leaned in to my ear. “Your dungmer attracts noise as well as fleshflies,” she noted with her barbed tongue, eliciting a rasping chuckle from the lizard. “Perhaps Kishra-do will offer him a chiming bell to wear so he might alert all the woodland beasts?” I was about to explain we’d face no dangers in this neck of the woods, when a hissing squeal interrupted her insults. Kishra-do leapt up, swiftly reaching for her staff, and brought it down with considerable force, piercing straight through the head of a huge rodent. Its tiny red eyes glared up at us for a moment, before Kyne gathered up the skeever’s spirit to give to Peryite. I narrowly missed receiving a furry face of jagged yellow teeth and disease, as a skeever leapt out into our clearing. Three, perhaps four, encroached on the camp, probably attracted by the fire. Or the lumbering nocturnal noises of our Orc friend. He attended to a skeever by bringing his hefty armored foot down, driving both boot and beast into the soggy soil. Ingjard’s arrows finished the rest of the vermin. Fenrig barely looked up. A brief and rowdy lull between conversation. “How so, idiot?” Kishra-do responded. A little harshly, I felt. “Ha! I’d wear your coat as a winter cloak if I thought you serious,” Bashnag continued. Ingjard looked up from her painting as I rose from my seat. Ingjard flashed me a look of concern, but I shook my head; these were the teething troubles usually present when others are brought to the hunt. The Orc waved the hindquarters of a charred skeever skewer in Kishra-do’s face. “You didn’t think you’d be eating your principal diet? How many different ways do you cat folk eat rat?” “None, you feeble-minded mongrel. We refrain from playing with balls of yarn, and mark our territory with flags, not secretions. Though I’m happy to make an exception with you, yes?” “Fellow hunters!” I stood to my full height. “Your bickering, though amusing, offends Kyne.” I produced a bottle of Ashfire mead (it seemed apt, based on our first destination), and handed it to the Orc. For the Khajiit, a skin of Moon Sugar double rum. “A spot of Nord diplomacy?” I offered.

A SSASSIN BEETLE | We spied the Ashlander camp at dusk; it sat in a patch of flat ground -- rare to encounter in the jagged wilderness of Stonefalls -- pockmarked by small rocks and twisted, stunted trees. Fenrig approached with a lit torch. His suspicions (and his dogs' heckles) were raised as he lifted the draped folds of a tent, and was almost knocked back by the smell. Dragging out a Dunmeri corpse, he had little time to examine the deep puncture wounds before Fang began to growl.

Something large was shuffling about in one of the other tents. A faint clicking, rasping sound could be heard. Mauler was bounding into the tent at full tilt. Fenrig barely had time to unsheathe his sword before Mauler was set upon by the first assassin beetle. We waited for his call, but he decided to face both insects with his dogs. Mauler soon tumbled out of the tent, attached to the carapace of this huge, scuttling foe, a mass of black, red, and highlights of gray. Mandible snapping and lunging, the beetle caught the hound with a deep, gouging bite, sending it yelping from the throng. Fang clamped her teeth on the edge of the beetle’s armored hide and wrenched it upwards, attempting to flip the insect onto its back (as she’d been trained). The beetle lashed out with its frothing jaws, biting the air close to Fenrig’s cloak. Clamor, as Bashnag had to be restrained from charging in to wallop a second assassin beetle as it scuttled from the same tent. It immediately disappeared. Moments later, the bug blinked back, behind Fenrig, and leapt at the Nord’s back with mouth snapping. Fenrig’s senses did not fail him. He wheeled round, catching the underbelly with a wrenching, skewering rip, then stepped to avoid the heavy shower of the beetle’s acid-laced blood. He turned back just as Fang tore into the carapace, the beetle writhing and wrong side up. Another sword plunge, and the mystery of the deserted Ashlander camp was solved. We found no evidence of a hive, and so burned the remains of the Dunmeri wanderers. While Footfalls-in-Snow merrily scooped out the hollowed shell, Bashnag cooked up the beetle stew. It could only be described as “mostly digestible,” despite the Orc’s assurances of his competency in the kitchen.

C ORPRUS HUSK | The lights of Bal Foyen appeared, twinkling through the ash haze, choking the river winding to little more than an ooze, slowly flowing past this site of ancient Dwemer origin. Red Mountain, and its numerous smaller eruptions, have certainly stunted the vegetation and made life intolerable for the Dunmer. This is a land of permanent gray. Our slog was slow going, the ash particularly deep, and time seemed to pass with a weary malaise. Or, as our Argonian friend put it, “This is a place where even the rocks have sorrows.”

Moist face shrouds (or continuous nose picking in the case of Bashnag) helped the breathing as we traipsed to firmer ground, and the cobbles of the road to Bal Foyen. Our benefactor, my Skald King, and our firm alliance as part of the Ebonheart Pact prevented us from wantonly engaging in combat with the Dunmer. This was a ruling even the Orc was willing to follow, which made our subsequent combat so unintentionally deadly. Masser and Secunda were rising and the valley was bathed in an eerie light. Now that the winds had died down, we heard very faint bustling from within the distant town, noise echoing along the rocks. Fenrig was on a high ridge, seemingly preoccupied with stargazing. But he gave a quick succession of sharp whistles, and pointed to an area of thoroughfare unseen by the rest of us. Three Dunmer… wearing fineries… seemingly lost. As we rounded the corner, we spotted Fenrig’s quarry: an overturned carriage. Horses mangled and slid into a ditch. One Dunmeri noble, pinned under a wheel, had expired. We raced to their aid. The three thin shadows remained deaf to our initial greetings, content to amble in an irregular movement. Another was spotted in the rocks, and Ingjard raised the alarm, and her bow. “Corprus husks!” she cried. I gestured for her to slow her aim, and advanced to the nearest Dark Elf to check. It turned, and the moons’ glow lit up a face of harrowing deformation. This was a wretch who had long since succumbed to the horrors of corprus disease. Like his housemen, he was a mass of overstretched skin, torn and ripped to contain clusters of purple-colored boils, some burst and others throbbing. Innards could be seen within flesh holes; it was a wonder his guts hadn’t spilled out yet. A leg expanded with tumors, flesh woven into once-expensive breeches. A turquoise grotesque, shambling in the moonlight. Our shrouds were pulled back up. Commotion: The sound of vomit chunks pattering off the Orc’s shield, as two of the husks lunged at Bashnag. “Grundvik!” the Orc yelled. “Your treaty extends to undead Dunmer?” I answered with a well-aimed chop of my aze, which brought my adversary to his knees. Footfalls-in-Snow replied that, in fact, these weren’t to be considered undead, and were tangibly still living victims of a purulence active in these parts. “We make an exception this time!” I yelled over the rambling Argonian, as my axe blade severed the husk’s neck, and my shield saved me from the fountain of blood and sputum. Bashnag’s victims were a little more advanced, one drooling trails of purple bile as it swiped lazily at the Orc with an engorged hand. The Orc pushed it back, yelling for advice. “Was I not clear? Send them to Mauloch!” I shouted. Bashnag swung and glanced his target in the jostling. The putrid bag of sagging bones looked at him with a baleful expression, and emitted a cloud of loathsome vapors. “Cover your face, mighty oak!” the Argonian advice came late: The husk burst apart, drenching Bashnag in a mist of pox and internal juices. He managed to knock his other foe clean off the ground with a furious wallop from his oversized mace; the Dunmeri husk fell apart in the air before dropping into the river. We had survived the husks, but the Orc may need to be killed in his sleep.

K AGOUTI | Back into the choking gray clouds of Stonefalls we go, searching for indigenous hides to strip from the backs of lay beasts and sell for leather. This is a land seemingly cursed by fire and the constant belching of ash from the mighty Red Mountain; we tread ankle deep in dust, along the great crater. Tracking is difficult, but Ingjard is explaining the more subtle methods of locating prey to Bashnag under these conditions most inclement. Her willingness to teach is commendable, but her pupil seems to be here with a single purpose: to cave the skulls of those that harm our party, and to cook the flesh of the edible ones. Widening his knowledge seems almost insulting.

Amusingly, it was Bashnag that first trod on evidence of kagouti activity. As he angrily wiped his boots clean, Ingjard examined the spoor more closely. Then she was off, following the trail up towards a ridge of rocks and stunted mushroom growths. I explained the differences between a kagouti and an alit to Footfalls-in-Snow; the two beasts share a similar collection of bones and toughened flesh, but the kagouti is larger, its back ridges more plated, with tusks missing from its smaller cousin. The alit may lack the stature of the kagouti, but the scars across my arms (from my youth, when I ventured into the Velothi Mountains to hunt these easily slain critters) reveal a more vicious temperament and more cunning attack instinct. Ingjard motioned for me. I ascended to her side, and spied three kagouti (I instantly remembered their stumpy legs and tail) further an otherwise-deserted caravan route below us. A fresh corpse, that of an alchemist, was being played with. Tiny, gleaming red eyes peered out below a helmet of plates. Snorting triumphantly, drool hanging from its fanged a drooped slack jaw, the largest kagouti charged the dead Dunmer, ramming into the body and using its tusk to scoop up its prey. The merchant landed in a mangled heap, and lay twitching. Fenrig was summoned to position himself for an ambush, and he quietly split apart from the others, with his dogs skirting the merchant’s path below to a vantage point of sharp boulders across from us. The kagouti had bitten down into the still form of the dead Elf, ripping open the alchemist’s guts as it began to separate sections of Dunmeri meat for its lesser brethren. I nodded to Fenrig and we readied our bows as Ingjard slid down the embankment, shield and axe at the ready. The kagouti bull turned and roared at her, beginning a charge that ended with Ingjard’s shield taking the full brunt of the kagouti’s heavy head. Ingjard staggered back, her axe already swinging. The kagouti dropped its head, and the axe scraped off with only a nick. Her second swing was more successful; as her axe dug up through its chin, the kagouti’s eyes bulged and it sank into the ash floor with a wheeze. The lesser kagouti had already fallen to our arrows, sent (with Kyne’s blessing) between the plated armor. As kagouti hide dried on our racks, Fang was growling at the Argonian again. Then hissing, which I hadn’t heard before. Footfalls-in-Snow, it seemed, had befriended a lizard creature, which had taken to its new master like an Orc to violence. This was a scuttler: a more dog-sized, docile, and intelligent cousin of the guar, but not as tasty. It was snapping at Fenrig’s hound, raising its back spines and flaring its neck ruff. I nodded to Fenrig, who snapped his fingers, and Fang slunk back to his feet, while the scuttler rubbed the Argonian’s legs and made an odd cooing sound. There’s a fine line between pets and pests, and that Argonian may have crossed it.

K WAMA SCRIB, WARRIOR, AND WORKER | Our Argonian retainer volunteered for scouting work this morn, and despite Fenrig’s grumbling protests, I gave him the chance to scour the volcanic gloom for signs of a kwama colony. Not five minutes had passed before the lizard returned, deftly dodging Fang’s growling snaps (those war dogs aren’t fond of anything scaly, it seems), and dropping to his haunches at my tent. He quickly sketched a map in the ash, showing a narrow opening to a large cavern alarmingly close by.

Fenrig entered, and gestured with a dismissive wave, “We trust the hunt of this scaly fellow?” Footfalls-in-Snow peered up from his haunches as Fenrig continued. “Grundvik, your map vanishes with the wind. The same fate awaits us if we wander down a lizard’s path.” Ingjard asked what was vexing him, and Fenrig stepped in front of the Argonian, seeking a more private conference. “Between us Nords and Kyne? My dogs don’t trust him. That means I don’t trust him. This area is filled with fissures and loose scree, where a scaly hand can push you to meet Orkey. Where’s the evidence of a kwama nest? My dogs don’t smell any.” “The ash particles block your dogs’ noses, friend.” Footfalls-in-Snow spoke softly as he untied one of his many bags, and threw the still-twitching head of a kwama forager at our feet. “And this isn’t a trick of the light. I harvest kwama eggs in Black Marsh.” Before Fenrig could respond, Bashnag poked his head and considerable shoulders through the tent flap. He was grinning like a madman meeting Sheogorath. “My bearded friends! And the stonefist woman!” The Orc waved his gauntlet excitedly. “The lizard must be a magician, as he’s conjured a real force to test us! Large, brown insect men approach! While Mauloch commands me to slay them all, I might need—” Bashnag’s voice was severed as a broomstick-thin arm attached to an angular claw closed around his throat, and he was pulled violently outside. As tall as a Breton, but far less likely to utilize cunning political diplomacy to settle territorial disputes, the kwama are a hive-minded plague of giant insects sculpted by Kyne in shapes of varying grotesqueness. The Argonian was obviously right; we were being swarmed by warriors, the defenders of the kwama colony’s burrowing tunnels. Thin but powerful forearms, clad in plates of natural armor that extended around the neck and down the back to a rattling thorax, with a hunch and a head of further plating, out from which poked a small, snapping pincer mouth and two beady eyes. We were blessed by Kyne’s generosity; I had never seen as many of these foes in one place. We’d have our pick of the spoils… if there were any of us left to claim them.. Our predicament was now less of a hunt, and more of a pitched battle. Normally, Bashnag’s wanton bludgeoning resulted in less-than-pristine ingredients for our benefactor. But such was the choice of kwama scurrying over the gray rocks, I happily watched him cave in the skulls of a half dozen kwama warriors, as his red mist descended and his combat degenerated into a mass of flying limbs (some detached) and sickening crushing sounds. I ran to higher ground, introducing two slavering kwama warriors to the sharp end of my axe. Fenrig whistled, but this wasn’t for the benefit of his dogs. He was forcing his way into a secondary entrance, which had far fewer warriors defending. Fang and Mauler seemed to be enjoying themselves as they hung onto various kwama appendages before their master finished their foes with an arrow. We met at the entrance, causing the warriors to retreat into the fissure crack where our Argonian first spotted them. Into the nest we descended, finding the passageways empty, until we found a hatching cavern large enough to accommodate us (and Bashnag’s wide-reaching combat style). A clattering of insect feet was heard further down the passage. As the Argonian began plucking eggs from their fluid sacs, we readied our ambush. A confused kwama worker scampered into our trap, and let out a shriek when Fenrig’s swift axe connected. Staggering on its four legs, this dog-sized mass of curved head plates attached to a bulging, segmented body and four unsteady but talon-tipped legs lunged for Ingjard. She sidestepped the worker, missing its poisonous, snapping mandible. Those mouth talons helped carve the tunnels we were fighting in; Nord bone would crack easily between its teeth. Fortunately, instead it fell to numerous Nord arrows, and deflated. More scurrying sounds, and a couple of scribs (recently hatched larval forms) scurried into our chamber, along with more warriors. They shared the same general appearance as their larger, more upright brethren, but were far less dangerous. Unfortunately, Fang’s overeagerness to leap into the fray allowed us to witness the scrib’s only real means of defense: it managed to connect with a lunging bite, slowing the dog to a paralyzed stupor. Had this been a swarm of scribs, Fang’s malaise would have overwhelmed her. We quickly changed to our axes, blades, and hammers, and readied for more. Bashnag was holding back the warriors with rabid glee. “Mauloch drinks your blood!” he yelled between prods, pummels, and wild mace swings. As Footfalls-in-Snow and Ingjard began to drag the scrib and worker corpses back outside for stripping, Bashnag adjusted his chin guard after a kwama warrior a little larger than the Orc’s previous victims clambered over the pile of insect bodies and caught Bashnag squarely in the jaw with two swift punches, augmented by a crackle of magical energy. “You hit like a forge wife!” Bashnag retorted, as he staggered back, allowing the warrior to scrape the ground with its talons, and swiftly stomp the dirt. Up shot a sharp spine of hardened ash, gashing the Orc in the leg. This eruption was not to last; Bashnag unleashed his fury, grabbed the warrior’s head, and twisted it apart from its humped shoulders. Thick ooze coated the Orc and the walls of the cavern. The remaining kwama swarm watched their champion’s decapitation with uncertainty, allowing us to roll a boulder to block further investigation and hasten our escape. We retreated back into the Ashlands, dragging our corpse loot away from the colony’s clutches. Although Bashnag would have merrily fustigated his way to the kwama queen herself, we had all the eggs, meat, and leather we needed. While Bashnag stitched up his leg, I asked the Argonian how the extraction of cuttle (the waxy extract from within a kwama’s beak) was coming along. Footfalls-in-Snow rummaged in one of his many carrying satchels, and produced a strange tool, flat and smooth at one end, with sharpened, barbed edges at the other. “This is a t-thuk, in the tongue of my egg brothers,” he said, showing me the correct way to grip the device. “It pries apart bone as a Colovian burns a forest: quickly and without much forethought.” Taking the dismembered kwama heads from Bashnag’s collection bag, the Argonian swiftly jammed the instrument up through the beak palate and cracked it open, and raw cuttle spilled out onto his catch cloth. He flipped the tool and used the sharper edges to scrape any remaining matter still embedded within the beak. Then he repeated the process with the other intact heads. A most impressive scavenging technique: his method meant there were no skull shards to pick through, and the cuttle remained moist before sealing in our merchant jars. The Argonian proved his usefulness for a second time today.

A LIT | The ash winds died down a little as we passed into the fertile plains of Deshaan, thankful to breathe clear air. We followed a gloomy trader’s path interrupted by the green glow of marker lanterns. As we skirted Mournhold, we decided to hug the edge of the fungal forest. My concerns for Footfalls-in-Snow grow as a wart on the nose of a hagraven; he seemed mesmerized by the glimmering mushrooms. I requested he not lead us into a mire. He beckoned me over, and pointed to the tracks we’d been following, gesturing to a grazing area of short grass and loose boulders.

“Alit. Beware; they are not without teeth.” Alit leather is highly prized by Ashlanders, and more so by our benefactor, but we were halted by the Argonian; he wished to face these creatures alone and prove his mettle. We watched as he crawled towards two thickly set walking mouths, squat, scaled, and ferocious of claw. Beady yellow eyes darted, and nostril slits embedded into a mottled green mantle sniffed the air nervously. Soon after, a shrieking roar from the larger alit signaled the Argonian’s ambushed had failed, as the beasts split from their feeding and circled our tracker, in an attempt to surround and bewilder him. Footfalls-in-Snow charged at the bigger alit; it dug its oversized claws into the ground and braced for the Argonian’s dagger, which struck the beast behind the eye. A shallow wound, but a hit nevertheless! The smaller alit leapt, attempting a rip to the face, but our lizard friend ducked the attack, and drove his dagger into the neck. The beast slumped forward, deflating like a punctured bladder. The remaining alit chose an inopportune moment to widen its mouth into a roaring bite; the Argonian plunged his blade directly into the maw; the alit choked and writhed as spittle and blood sprayed the grazing grounds. “You’re looking a little green around the gills,” Fenrig remarked with a smile. Fenrig’s moroseness has lessened in recent days. Perhaps our Argonian friend is more of an asset than I first realized.

G UAR | We are guests in the land of the Dunmer, and although some of the greener-tinged members may not act with appropriate veneration even without mead flowing through their veins, we must respect the Dark Elf and their way of life. Passing into the realm of Deshaan, we encountered farms of grazing guar, one of the many oddly proportioned, bulbous-headed creatures that are bred as pack animals or mounts. Our descendants will not sing songs about the triumphs of a band of grubby poachers. Kyne would not smile fondly on our steadiness with a bow when aiming at a chicken or a goat. So we hunt feral guar across the ribbons of windswept grass.

Fenrig’s dogs picked up the scent and stayed a respectful distance away from our kill; their master is an exceptional shepherd. Slightly darker, marked with scars both old and fresh, and lapping at pond water near a meandering stream, Fenrig’s dogs crept away, while he produced a finely forged blade and equally robust shield. The guar, looking up with tiny forearms tucked in behind its bulging snout, gapped teeth lining its dribbling mouth, spotted Fenrig and hissed. The Argonian’s scuttler twitched and hissed back, and I shot a glare for the lizard to stifle the noise. Hardened feral head hit tempered iron shield as the guar turned from a trot to a sprint, sending Fenrig reeling onto his back, his weapon dropped. The guar attempted a mighty leap, landing atop Fenrig, where the beast’s intermittent rows of stumpy (but sharp) teeth darted and snapped into the Nord’s forearm, glancing off the armor with a clang. Fenrig soon regained his composure (and his sword), stuffing the full length of the weapon up to the hilt through the guar’s exposed belly, which ripped apart as a feast of internal parts tumbled out, splattering the ground while the guar squealed and dropped atop its bits. Mauler and Bashnag both licked their lips, although the Orc wait longer for his meal. The dogs feasted on offal and bones while the Argonian stripped the hide from the corpse. It hung to dry as we enjoyed slightly tough (but eminently edible) roasted guar fillets. Fenrig abstained from eating, with a faraway look in his eyes.

B ULL NETCH | The Ashlander camp was partially burned. The guar pens were broken, with bodies of livestock strewn and scattered about the grassy plain. A family of netch were huddled together above a small lake, close to the burned-out tents and charred Dunmeri corpses. Ingjard reckoned the dead were on the march in these parts. Footfalls-in-Snow noted that netch leather and jelly were on our list to gather. Our slaughter work was seemingly done, but upon closer inspection, the netch corpses had been baking too long in the sun, and were bubbling with putrefaction. The leather was salvageable, though a fresher kill was needed.

While Fenrig began to skin the rotting netch, we advanced to the lake to view a bull, a betty netch, and two calves. The larger of these hovering beasts was growing increasingly agitated, and its internal propulsion sacs were pulsing with vapors. We covered our noses, slowed our breathing, and advanced, coaxing the bull away from its family with a precise Argonian arrow up through the soft underbelly flesh. Bashnag was seemingly unprepared for the slap he received, and seemed surprised to be on his back, coated in a cloud of poison bloom the bull had violently shaken out as it pressed the attack. Scrambling back with a splutter and a wheeze, the Orc managed to place a mighty swing of his obscenely sized mace right into the netch’s side. I heard a crack as the netch wobbled, its tentacles shuddering, before it retaliated, violently plunging its arms down into Bashnag’s unbalanced form with a focused thrust. The Orc staggered back in the shallow waters, spat out a tooth, grinned, and swung his mace in a great arc once more. The hit was impressive, crushing hide and bone, and the bull dropped from the air with a thick, wet thud. The Argonian was at the body with a carving knife before the bull had stopped twitching. “We feast well tonight, lad!” Bashnag shouted at me. Siphoning the glands for its jelly, Footfalls-in-Snow quickly and patiently explained that netch meat was mostly poisonous, and less appetizing “than the toe fungus from a spriggan.” The Orc muttered something about “rather gnaw on Witchmen bones anyway,” and stomped off to apply antidote to his ingested blight.

N IX-HOUND | Among the rocky outcrops littering the plains of billowing grass, Fenrig first found the tracks, close to a pile of old, gnawed bones and the rags of an Ashlander. “A pack of five, perhaps six. Down into the mushroom woods,” Fenrig pointed to the trees swaying in the breeze, their twilight shadows lessened by the faint glow of the giant fungi poking up from the forest floor. He whistled, and Fang went bounding down into the bushes, closely followed by her furry brother. Bashnag was feeling better, and even recognized the footprints of a nix-hound; he recalled driving them out of King Kurog’s animal pens in lower Wrothgar. “They’re as fast as a wolf, but are too simple minded to flee a fight they’re losing,” he explained.

“Perhaps a description of a certain Orc I could mention?” I thought, but decided not to utter. Instead, I remarked that I was surprised these creatures had made their way so far west. I was less surprised that the Orc hadn’t heard of the alchemical qualities of the beast’s meat. Perhaps the horribly bitter taste had put him off? The Argonian confirmed nix-hound flesh, a small amount of blood, and “at least four intact claws” were required by our benefactor. I requested that Bashnag keep his bludgeoning to a minimum until our quota was met. The moons were large and glistening as Ingjard adjusted her bowstring, and the bird song and forest voices quietened, replaced by the faint sounds of rustling. Then commotion in the damp undergrowth. Extending our hunting tendrils out to surround Fenrigs, his dogs, and our prey, we encroached on a clearing where Fang was staring, back arched and fur up, at a spindly looking creature, all sharp claws and hooked knees, a serrated, insect-like back, erect and threatening, with a crown of armored skin above a revolting face with pink, cloudy eyes of differing sizes embedded between quivering mandibles, dominated by a sword-shaped snout. It emitted a baying shriek as it saw its chances of a meal dwindle, and leapt at Fang anyway. It landed behind Fang; its nose swung and scraped the dog’s hindquarters, before the Nix-Hound was put on its back permanently by one of Ingjard’s arrows. Fang began to pad forward with jaws open to play with the corpse, but a quick whistle from Fenrig kept the corpse intact. The perimeter of the clearing shimmered slightly. Three more nix-hounds decided to end their lives on our armaments. One found the only opening in Bashnag’s armor, mounted the Orc, and began quickly leeching the blood from his neck. It was merrily gulping down fluids until it felt a gauntlet around its throat. Too late I shouted to the Orc to keep the body intact; it was thrown to the ground with enough force to wake a sleeping draugr, and squashed under mace and armored boot. A collection of protruding bones and indistinct offal remained. Fenrig and Mauler fared a little better, his sword clashing with nix-hound nose before the head was lopped off with the type of clean, quick precision I’d expected of a Nord. Ingjard was slightly perplexed as her target blinked from existence behind a tree, only to reappear behind her, rearing up for a stab to the back. I brought my axe across the back of the last nix-hound, severing it completely. Mauler lapped up the blood as I brought out my vial and daintily filled it with the blood we needed. Our meal was easily forgotten; nix-hound meat is sour as a jilted Breton queen. Footfalls-in-Snow was simmering some mushrooms from the Bitter Coast, which helped mask the taste somewhat. Bashnag rubbed his neck vigorously. “By Vivec’s curse, is there anything we’re hunting in this infested province that won’t give me an itch, cough, or droop?” “Do not tremble, tiny leaf,” Footfalls-in-Snow replied, “for you have finally stopped soiling yourself; the Afraid Wind lessens to a mere draft. Your illness vanishes on the breeze.” Us Nords stopped our low murmuring and Ingjard reached for a mead bottle. “Your rudeness displeases Mauloch greatly, lizard,” the Orc retorted. “Perhaps the only delicious creature in Morrowind is an Argonian? Would you share your tail with us, lizard? I hear it grows back.” The Argonian peered up at the Orc over the steaming cooking pot, and gritted his teeth. “Unlike a wasteful Orc, Argonians use every parts of their prey. Your skin would make a good drumhead.” Bashnag’s laughter echoed across the plains. It was fortunate that the Orc hadn’t realized the Argonian’s hackles were up.

|